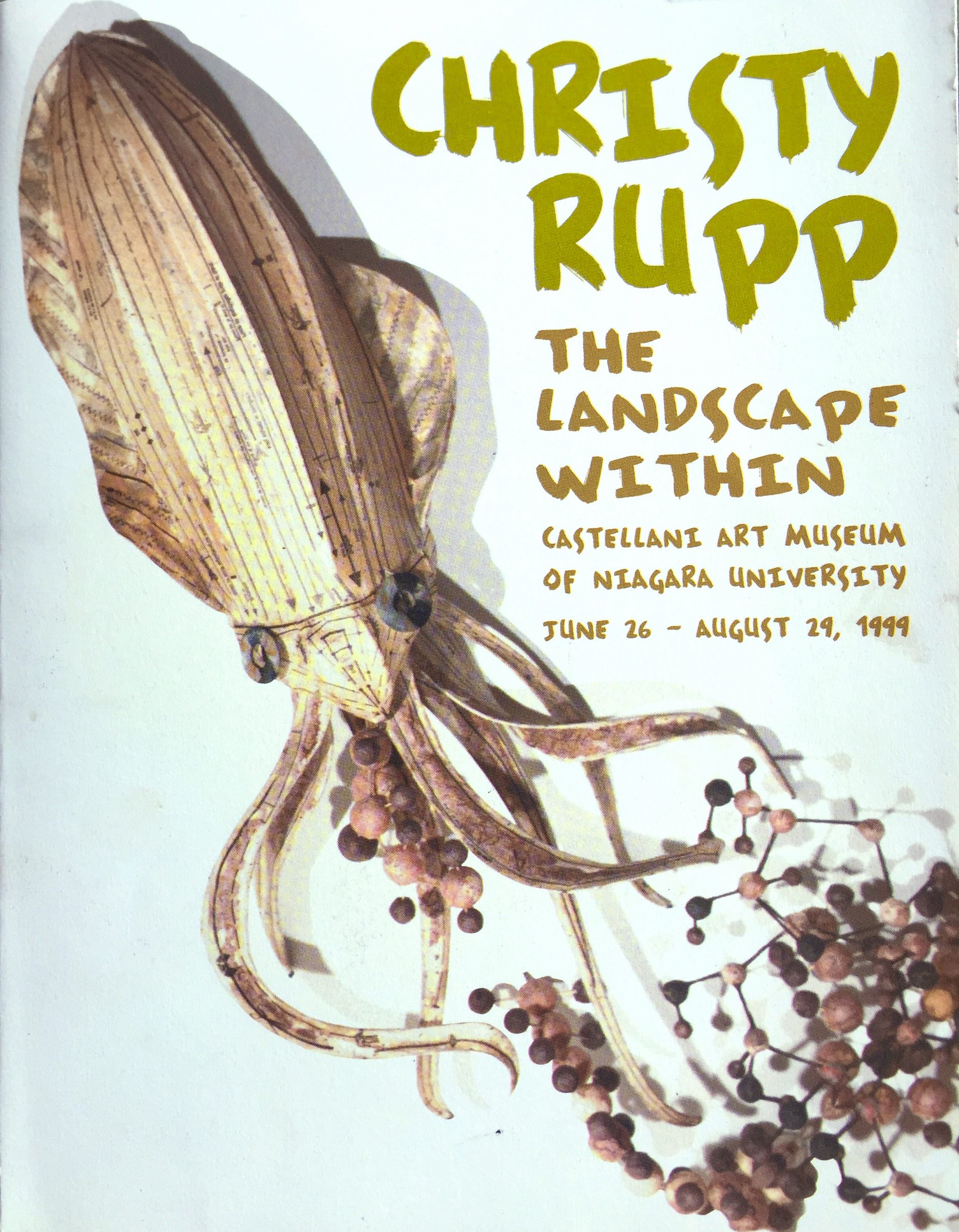

the landscape within

essay by chris kraus

Is the Cell a Happy Place?

By Chris Kraus

For many years, Christy Rupp has used living organisms as metaphors for human situations and behavior. Her creatures aren’t cartoon-cute. They are themselves. In 1979, affiliated with CoLab, a loose collective of pre-East Village artists, she burst upon the New York City artworld when high minimalism was in vogue with a piece called Rat Patrol.

It was the springtime of the New York City garbage strike. Trash piled up outside of buildings, on the sidewalks, clogging sewers, in the gutters. Post-bankruptcy New York became a mammoth site-specific work of scatter art. Rupp stole the image of a rat from a subway information poster. She made 4,000 posters, hung them all over Manhattan, very low to the ground. The garbage strike became a metaphor for the chaos of the city during the early days of gentrification, when empty buildings were being warehoused, the first step towards elimination of the poor. Of course things would get much worse, although at that time, who was to know? The garbage strike was a radical demonstration of a rampant uncontrollable equation: a population multiplying and consuming within a finite space with no place to put its garbage. On May 15, a pedestrian was attacked by a pack of rats, leaping from a dumpster. All that spring, rats ruled.

Christy Rupp has always been a social scientist. She’s not exactly a “political” artist because there’s never any commentary or polemic in her work. Rather, she is literally political. Rupp has undertaken to examine certain systems to find out how things work. Beautifully constructed and deviously analytic, Rupp’s sculptures crystallize complex social circumstances into metaphors as clear and frightening as fairy tales.

The pieces in this show examine environmental poisons in the places where they really live: the active cell. Is the cell a happy place? Rupp’s research shows the cell to be a place not unlike Aristotle’s vision of the city, a fragile membrane capable of encapsulating warring molecules in provisional détente. What happens when this balance is disrupted?

Enter Olestra—the fat free molecule, engineered in a high-tech corporate food lab, a gateway to the paradise of consumption: with it you can eat yourself to death. Injected into potato chips and other “fat-free” fast foods, Olestra attaches long chain fatty acids onto a sugar molecule. The molecule becomes engorged with plastic to the point that it’s impossible for the body to break it down. Wrapped in Olestra’s methyl-esters, fat molecules become too large to be absorbed and so must be excreted before entering the bloodstream. Newly consumed sugar and fat molecules are thus transformed into something like the Blob, rolling through the organism, prematurely eliminating vitamin A and Beta-carotenes, and many other of the body’s vital nutrients along with it. It is an ethnic cleansing of the body, as the cell is stripped of it’s immune system by removing all molecules of fighting age. The molecules that remain are vulnerable, to cancer because they lack nutrients to fight for them. Olestra makes it possible to have it all: to eat continuously and still starve.

In Rupp’s sculpture, the digestive system is depicted like an old French horn. In keeping with the philosophies of Western medicine and market capitalism, the makers of Olestra are isolate and focused in their task: create a fat-free compound, irrespective of it’s impact on the organism. And so, the digestive system stands alone, its structure wrapped in sewing-pattern tissue paper. Olestra offers women freedom to remold their shapes to a new pattern by eating fat-free food. Food goes in; burnt and blackened poisons emerge from the other side.

In Octane, a ten-legged crab becomes a type of typhoid Mary. The crab itself remains immune to petroleum bi-products, poisonous chemicals frequently emptied into bays. Its flesh becomes a breeding ground, a point of hyper-accumulation. The crab lives at peace with the invader. Like other toxins, Octane seeps into a lowly host as a means of moving upward through the food chain. Humans who eat Octane- contaminated crabs get sick.

The sculptures in this show are exquisitely constructed, their muted colors and fine details reminiscent of a 19th century naturalist’s etching. Rupp creates three-dimensional metaphors for the deadly duality of food technology and economy. The Clean Water act, which gives us water that is chloride-clean to a point where it can no longer support life. Her sculptures show deceptively pretty poisons erupting from below a placid surface. Animals seem to leap outside their bodies. In fact, they’re chained to the ghosting-presence of the chemicals that invade and now compose them. Living organisms exist in parallel-time with chemical half-life. And yet, on the surface, everything seems fine. In Politics, Aristotle set upon the organic model for the functioning of the city-state. Everything proceeds within concentric rings of social order: family, household, village, city, state. In The Landscape Within, Rupp drastically updates this. Organic life remains a model, and yet organic life is now hopelessly consumptive, chaotic, cancerous and skewed. This collection of objects ups the ante of all Rupp’s prior work to date by showing matter that is culture existing pleasurably within a periodic table of decay.