Runoff, 2024–2025

Essay: Space of Waste

Our garbage creates, changes, or destroys the habitats of other beings – habitats that are as intimately connected to our own as our breath is to our bodies. Rats run through our trash bags, nibbling our leftovers, forging an interspecies urban architecture around our drains, our dumpsters, and our service tunnels. Seagulls pick over our landfill sites and hermit crabs make their homes in barnacle-encrusted tin cans on the ocean floor. Chemical spills poison our waterways, while agricultural run-off makes them bloom with bright swathes of algae, a proliferation of green life while fish and frogs gasp for oxygen. Earthworms swallow microplastics and bacteria become resistant to surplus bleach and antibiotics.

We are not “supposed” to see all this. Every day, our waste is gently snatched away from us by convoys of lorries, municipal street cleaners, storm drains, and chutes. This happens before we can see what we’ve done, before we can comprehend the magnitude of the rubbish we are producing as a society. Out of sight, out of mind, we are told. And why? Because there is money in garbage. Sack-loads of it. We are all living within the garbage-industrial complex.

Over the course of her long career, Christy Rupp has engaged with these questions of waste, visibility, and habitat. Working primarily with discarded single-use plastics, her sculptures tell a story of the vibrancy of all life, the interconnectedness of human and nonhuman ecosystems, and the power exerted on our shared world by waste. Informed by the emerging field of discard studies, Rupp explores the maintenance of power by dominant systems through which places, people, materials, and beings, are devalued and discarded.

Rupp is particularly drawn to the context of these questions in her home city of Buffalo, an area named after an animal that once defined many North American landscapes. The story of the animal and its demise reveals the power of waste – and particularly to the ways in which things are wasted not because they are valueless, but because they are valuable.

Under this way of looking at things, both colonialism and capitalism become systems of creating waste, in ways that are increasingly closely tied to the oil industry. In this exhibition, Rupp actively alludes to the destructive power of oil pipelines, as well as working with petroleum-based products such as various plastics.

Several pieces are beautifully crafted from defunct credit cards, where their overlaid shards resemble protective scales, an exoskeleton of hollow promises. Excess is encapsulated in the credit card, a form of plastic money that encourages a disconnection from reality in the same way that our garbage systems do. We borrow money to buy consumer goods, and when we do, we are rewarded with free flights; capital and oil are such companionable bedfellows.

In our relationship to the more-than-human world, Rupp suggests, we are borrowing against the future. We are blindly spending resources without recognizing their essential role as habitat, driving a spectrum of species towards extinction – perhaps including ourselves. We are buying things cheap, but in the future our debt will be crippling; while money is intangible and fluid, extinction is finite.

What will we choose to save, and who decides? Which lives will we label valueless and discard? And how will the legacy of our waste be read by future generations?

–Anna Souter

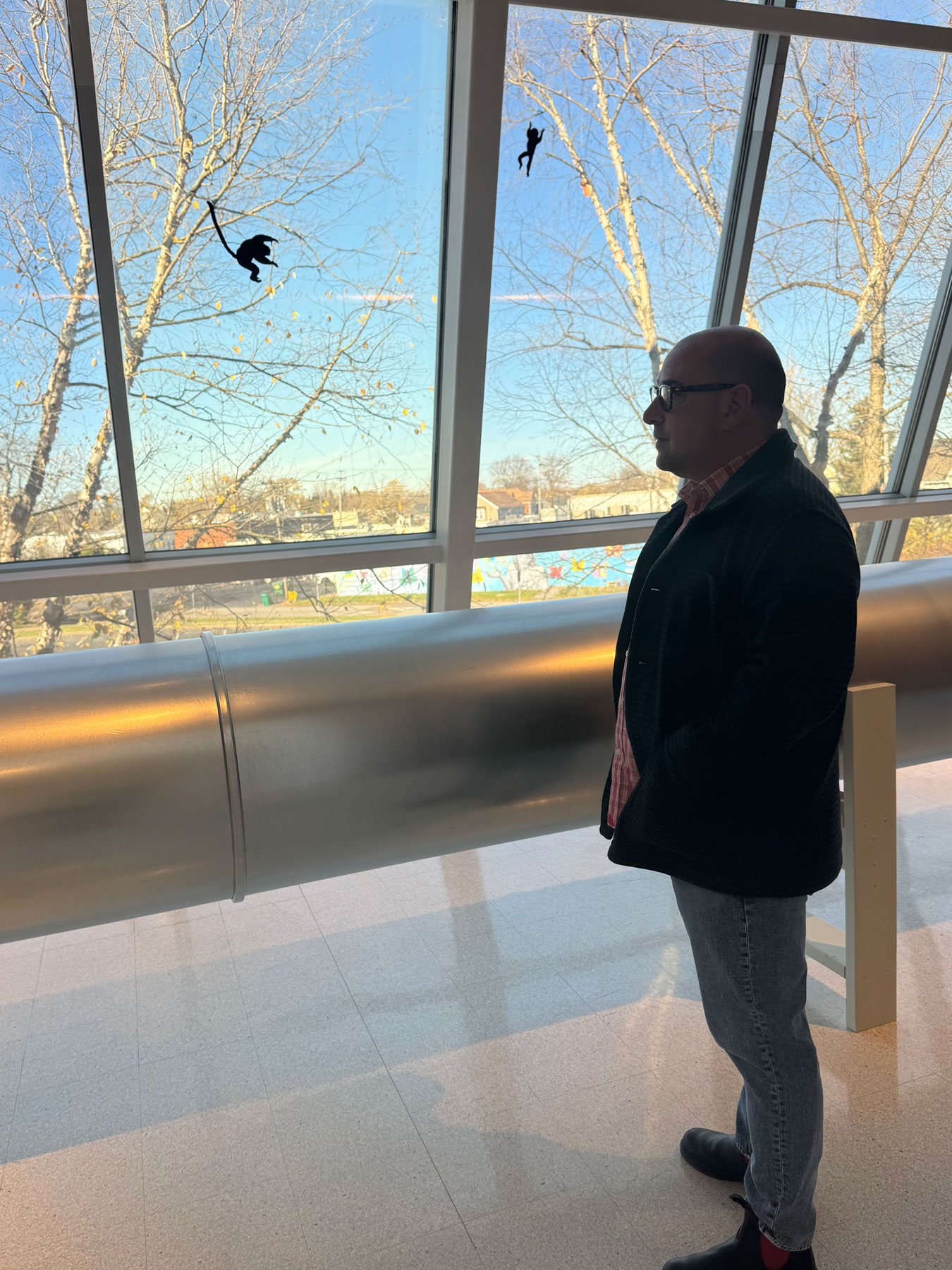

Installation Images

VIEW MORE IMAGES FROM RUNOFF

©christy rupp 1962–2025 | site by lisa goodlin design