Natural Selection: The Work of Christy Rupp, 1992, Burchfield Penney Art Center

“Christy Rupp: Natural History Meets Coney Island and the Sandinistas” by Lucy R. Lippard

[Reprint]

On the initial encounter Rupp’s sculptures are attractively endearing. On second glance, they are often grisly, even tragic. Beneath her humor lurks a knowledgeable and enduring anger at the loss, or rejections, of so many gifts from nature. Her cows have television faces, her iridescent fish are impaled on drain pipes or have their guts exposed, her spiraling shells are filled with ecologically poisonous substances. They mature from natural to B-movie horror-forms which are, alas, not fictional.

Rupp was raised in Buffalo, where the Pop art collection at the Albright-Knox provided the basis of her art education. She counts among her early influences Lee Bontecou, Jean Tinguely, Lucas Samaras, Arman, and Anne Arnold (who was her teacher at Skowhegan). Although she attended the Rhinehart School of Sculpture at the Maryland Institute College of Art, her real introduction to the world she would enter was at Artpark in Lewiston, New York, in the summer of 1975, where she assisted on the construction of outdoor works by Charles Simonds, Dennis Oppenheim, Alan Sonfist, and Jim Roche.

In January of ’79 Rupp’s interest in animal behavior led her to crash a papier-mâché plane in New York’s Federal Plaza, in an effort to inform the general public about bird hazards to aircraft. The sculpted plane and gulls picking through the wreckage were accompanied by maps, pictures, and documentation about the Jamaica Bay bird population, which feasts on local dumps and hangs out at the airports. Among the project’s consultants were the Linnaean Society, the FAA ( Federal Aviation Association), and the New York City Department of Sanitation. Offering a typically broad view, Rupp said the gulls were only a symptom of larger environmental problems and suggested “more attention be given to alternate means of waste management, such as the proposal by artist/architect Peter Fend for the manufacture and harnessing of the methane gas created in the dumps and surrounding landfill near the airport.” (City Wildlife Projects statement, January 15, 1979).

Later the same year, Rupp attracted attention with another “City Wildlife Project” focused on “pest/pet issues.” Just prior to a rat scare in downtown Manhattan, when police closed off a block near her home in order to poison the area. Rupp plastered the site, and the neighborhood, with posters of rats at ankle level, to warn passersby of the rodent colony. Her sympathies, however, did not lie entirely with her own species. Visually and politically, the rat images also highlighted the human threat—the piles of garbage that were attracting the rats and then the toxic response.

The press picked up on it and Rupp, already known in the art underground, had her first fifteen minutes of fame. “Rats are not terrorist,” she told Jerry Tallmer of the New York Post, “(They) are not inherently evil. They’re just animals like any other animals. They don’t come into the world meaning to harm man. I see them as part of the history of ecology, in the whole chain of things. It’s just that they’re out of control in the cities.” She pointed indignantly to a 1978 Cornell study of “New York’s Metropolitan Public in Relation to Wildlife.” “It’s all about bluejays and chipmunks. Which is fine if you live in the thriving city of Syracuse and have a father who drives you out into the country every weekend. But it’s not much good if you live on the Lower East Side and don’t have a father.” (NYP, November 29, 1980).

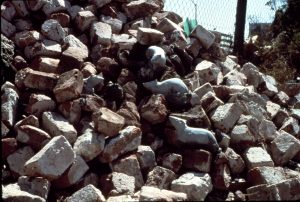

Rubble Rats, 1980

At the same time Rupp executed “Rubble Rats,” fixed in a heap of concrete rubble, and for a while her marvelous rat multiple sculptures became her trademark. More significantly, the rat pieces had led Rupp to examine city government. In the summer of 1980 she read Frances Moore Lappé’s mind- blowing book Food First, and the politicization process began in earnest. Rupp feels fortunate that it was her art that led “organically” (so to speak) into the development of socially concerned work and then to group activism.

In 1980, Rupp opened a “Deer Museum” in the Palisades Park forest “to illuminate the disastrous effects of the Bambi Syndrome, a Walt Disney-fabricated myth of nature, geared toward male supremacy in the wild, in which all predators are perceived as communists, animals are endowed with human emotions, and death never comes except as a villain. In reality, however, perpetual life for animals like deer means starvation, illness, and an over-crowded, decimated forest.” (City Wildlife Projects statement, August 1980). In November of 1980, Rupp constructed a “New York City Wildlife Museum” in a 42nd Street storefront, where art and animals cohabited, collaborating with artist, scientists, local schoolchildren, and the NYC Health Department. At the same time she made a videotape (produced by Chris Post and Peter Von Zeigesar) called City Wildlife: Mice, Rats, & Roaches which, among other highlights, showed rats being trained to detect bombs in airports and a tour through the digestive system of a cockroach (“nature’s garbage man”).

In 1981, Rupp made a piece under the Williamsburg Bridge as part of a project for Colab (Collaborative Projects). A new species (“NS Rupp”) was discovered hanging from the deteriorating bridge’s underpinnings. Made of smoke detectors, extension cords, dead umbrellas, and other urban detritus, they were eerie harbingers of increasing homelessness. Always expert at generating popular interest, Rupp called the newspaper as soon as the piece was installed to complain about it, the creatures were a health hazard taking people’s lunches and throwing garbage. ” I was thinking,” recalls Rupp, “of cities as resources, a positive look at things that don’t seem to be able to support life that can in fact support it.”

The political teeth of these relatively beneficent projects became more obvious in the next few years. Another early work was two goats knocking each other over. Their names were “Peace” and “Prosperity.” and they couldn’t coexist. In 1981, two “Commodity Cash Cows” named “Love it” and “Leave it,” with television sets showing statistics painted on their faces, were placed in the lobby of the Commodities Exchange as part of a “lobby art show” in downtown Manhattan. Their subject was the small-scale farmers losing out to agribusiness, and “what happens to land in this country, the way Big Business buys it and milks it, and doesn’t take care of it, and then moves on.” Rupp proposed a questionnaire to accompany the sculpture, asking what the commodities people thought about world hunger, but it wasn’t allowed by the buildings authorities. God forbid art provoke questions and move out of its static, passive niche.

The cows had originally appeared in a diorama at the Clocktower called “The Garden of Growing Chaos,” accompanied by an array of giant bonbons and a 3-foot coffee cup inscribed “Help! I’m drowning in caffeine!” The idea here was to expose the way agribusiness “ships stuff all over the place and leaves people hungry and enslaved.” The title referred to cash crops, export luxuries which are “not very good for our health.”

“Not Very Good for Our Health” could be the title of this retrospective. Rupp is merciless in pointing out the damage done by industry to the environment. In 1981 she began to concentrate on water and fish. “Delaware Park Lake Community” was a series of twenty-three biologically accurate cardboard fish. Then came the seven ” Acid Rain Brook Trout,” which initiated the increasingly horrendous mutation groups such as “Emission Fishes” and ” Nature and Revolution.” The latter’s striped bass and Coelacanth with PCBs were suggested by the 1985 fire at the Savon Chemical Company in Switzerland, which was extinguished with chemicals, inspiring all the chemical companies down river to dump their own toxins, killing the Rhine River and its wildlife.

Rupp found “Bottom Fishes” appealing because “their behavior is so much part of their anatomy, they have these sticky glands on their heads, they collect luminous bacteria and the little fish who are attracted are gobbled up.” This might have been the inspiration for the 1985 “Growth at Any Price,” in which a fish is swallowing another fish’s skeletal head, and “Corporate Merger,” referring specifically to the merger of R. J. Reynolds and Nabisco (“the oral fixation”), and all the other mergers in which junk bonds lead to bankruptcy and suicide.

“New Animal Patent for Brown Algae” refers to the patenting of a genetically engineered mouse which spontaneously developed cancer. “Rather than having these brown algae kills on Long Island to clean up the water,” Rupp suggests ironically, “maybe we should just invent new species that would survive. This fish, genetically engineered to come with a carbon dioxide tank, will be thrown away when his tank is used up.” In a different vein, “Iowa After the Caucuses” shows the rusty leftovers after all the political manoeuverings, like abandoned farm machinery, or abandoned farmers.

Other fish pieces demonstrated the birth defects brought on by pollution, their intestines are visible, or parts are replaced by a sewage pipe. For the “Acid Rain Series,” Rupp photographed a group of the fish sculptures on the banks of Lake Champlain where fish were “spawning in an area that’s overgrown with algae, so the plants compete with the eggs for oxygen and the eggs don’t hatch because they don’t get enough oxygen. Some have no sense of smell so they can’t tell when they are in heat, they can only spawn at a certain time, but they communicate by scent and all their senses are deadened when they water’s too acid.”

“Poly-Tox Park” in San Francisco, made in 1983, was a simulated toxic waste site, “a monument to our legislators and the people who get to determine the safe levels of toxins in our environment.” The premise was that some developer hastily buried these barrels, with their ominously stenciled numbers, and then opened the site to public recreation. The public was wary. The material was actually molasses barrels, but a banged-up metal barrel has become an insidious presence as consciousness rises about lethal abuse of industrial waste. Among other things, Rupp was commenting on the way artists are increasingly being asked to consult or build on suspicious places. (Artpark, for instance, is the East’s major public art venue, and it’s overlaid on a chemical dump site near Niagara Falls.)

Most of these works were made of painted cardboard, with which Rupp can work miracles. (A recent work, “Deconstructadon,” is a huge cardboard dinosaur skeleton, a pun on the planned obsolescence of art world theories.) Around 1983. however, she turned to steel for permanence, and found equally ingenious ways to avoid the ponderous “corten look” of so much public plunk art. In her hands, cardboard, pipes, throwaway metals and plastics are imagined into wild new lives. Like Mierle Lader Ukeles’ monumental paeans to urban trash and the San-Men who deal with it (which have been particularly important models for Rupp), Dominique Maseaud’s river cleanups, Cecilia Vicuna’s miniature “basuritas” (little garbages), or Ciel Bergman’s and Nancy Merrill’s non-biodegradable rubbish installation and ritual, Rupp’s sculpture beatifies the commonplace, giving the common its place in the sun.

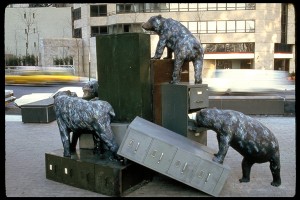

Hire Intelligence, 1980

Her first monumental steel piece was “Hire Intelligence,” installed in Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, New York City, in 1984. Rupp had proposed a piece about Central America, since the date coincided with works and shows all over town for Artist Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America. This was not permitted by the curator of the space, so Rupp did “the most playfully oppressive sculpture I could think of. I’d asked for January because I wanted it to be about the cold war, so it was just about paranoia and fear.” Four very life-like bears clamber around on seven steel file cabinets (drawers mostly closed) allegorizing the covert combat between CIA and KGB in the context of the UN. The punning title offered the clue, but the press release obdurately suggested a similarity to zoo environments and the ubiquity of filing cabinets in midtown. “Hire Intelligence” is now located in another war zone, at the Hunt’s Point Food Distribution Center in the South Bronx, a neighborhood under poverty stress and crack attack.

For several years, most of the polychromed steel pieces were small, and confined to galleries. But they raised increasingly large questions about the economic relations of the Third to the First World. In her 1986 exhibition at PPOW Gallery in New York, Rupp continued to attack pesticides, industrial pollution, unemployment, and corporate irresponsibility. This time she used a paradoxically small scale to tackle these giant issues. The small metal pieces suggest frames from an animated film about hemispheric economics. Titles like “Pestilence and Plague,” “Skilled Labor from Somewhere Else,” “Hometown Hunger,” and “The Worker Less Recovery,” (about the Reagan miracle in which “everybody could get jobs” . . . at Burger King for a minimum wage) led Roberta Smith to call them “three dimensional political cartoons” in the New York Times. This is not really an insult, but Rupp’s punning visual/verbal wit does evade the obvious.

Each of her sculptures has more dimensions than immediately meet the eye. And particularly important, in an art world that shies away from topicality, they come to grips with major social problems rarely seen in art contexts. “Uprooted Plant,” about runaway industry, is a factory building ripped up by its roots by a huge shovel—a painfully graphic image of de-industrialization in the rust belt. “Turtle Trying to Get into Its Shell” is a metaphor for “attempting to fit into an alienation culture that doesn’t work for you.” “Trickle Down” is a formally delightful illustration of Reaganomics with grasses, fish and supporting rod integrated into a delicate tower. The fish at the top nibbling from the algae gets the good meal, while the one on the bottom gets only an old beer can. An equally airy, zany, and tragic structure is the catchily titled “Runaway Factories Become a Bobsled—Rust Best,” which has the graceful intricacy of a Nancy Graves, plus content. (The belt moves and the factories turn into a bobsled with no brakes.) In “Unsolid States—Sub Machine Culture” which could be about the Third World or about Flint, Michigan, the guy lucky enough to get a job is impaled on the machine while a little sports car leaves the scene of the crime like a local dictator or corporate oligarch.

Other pieces in this series are more like one-liners. “Convalescing Staple Crops and Recreational Export Crops” is a series, including an ear of corn in a wheelchair while sugar cane zooms by in a convertible, and golden tobacco leaves luxuriating in a red plushy armchair before a fire, as well as “Rice in Traction,” “Cotton on Skis,” and “Coffee and Tea Play Ball.” Inextricable from these themes is the Latin American debt, which Rupp treated in the context of a show on the debt at Exit Art in 1988. Her “Harvest of Lost Shirts,” made just after the stock market crisis of October 19, is a lawnmower moving across a grassy dollar bill, the idea being that like a lawn, money is totally unnatural and human-made. “We should just forgive the debt because the dollar losses are just paper losses, they don’t represent anything more important than mowing your lawn on a Saturday morning, as this country sees it.”

In all this work, nature is the model and the forms have emerged from direct observation of natural processes. This gives them a unique edge, they exist between possibility and probability, the highest beauty and the most ominous ugliness. Rupp’s meditations on the theme of parasite and host are particularly pointed. Outraged about the wasteful consumption of lives and resources, she cites the space program as a prime example. (Despite promises of wonderful new technology, it became militarized, and ultimately socially useless.) In “The Army Runs the Government” (1985), a comment on El Salvador and Guatemala, a vicious-looking mosquito feeds directly from a disembodied heart. “Spear of Nations” is a revolver emerging from the dirt, a clump of grass growing toward the trigger. It takes its name from Umkhonto we Sizwe, the branch of the African National Congress which reluctantly accepted a strategy of violence against economic targets after decades of failed attempts at peaceful solutions to ending apartheid. Parallels to this course are obvious in the guerrilla movement in El Salvador.

One of Rupp’s most successful works is “Social Progress,” conceived just after her return from Nicaragua as a member of a Ventana delegation bringing material aid in 1984. A 6-foot snail hauls by a long rope a 17-foot long ear of corn that is being devoured by two weevils. Conceived for a specific site in New York’s Madison Square, it was intended as a tribute to Nicaragua, a small nation determinedly hauling much more than its weight, moving terribly slowly and involuntarily caught in a race with the parasites. As Mary Ann Wadden has pointed out, the piece “explores conflict in advancing levels. First is the conflict inherent in organic cycles of nature—insects and crops; secondly, the political struggles between societies and cultures—nations holding food hostage and finally the apocalyptic vision of a whole-earth conflict of nuclear war.” (Catalogue of C.W. Post College Public Art Program, 1988.) “Social progress is something that happens very slowly and with confidence and blind trust,”says Rupp, gleefully pointing out a photo showing “a bunch of people from the suburbs sitting on it and not knowing it’s about ‘Communist Nicaragua.'”

The piece was originally installed on the traffic island in front of the Flatiron Building at the busy intersection of Broadway, Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street, and was instantly popular with residents and workers who may also not have known it was about Nicaragua, but got the message about the pace of social improvement. Vandalism free, nicknamed “Shelldon,” it was the subject of fond and vociferous protests when the Community Board evicted it soon after Rupp’s six-month contract was up. Artists had hoped, as Jerilea Zempel put it in a letter to the Daily News, that “the popularity of Rupp’s work would be a positive counterbalance of the negative fallout from the Richard Serra ‘Titled Arc’ affair.” A News editorial (Nov. 30, 1986), citing “the thousands of people . . . who came to love him [sic],” and refuting “Snail foes” who wanted Social Progress to move on to make room for other sculptures (which, incidentally, never materialized), argued that “Shelldon had a wonderful central home. He deserved to keep it.” The piece eventually ended up in a bucolic site on the campus of Long Island University, forced into early retirement from its urban educational career.

In 1985, Rupp seized another chance to inform the public on her favorite theme when she programmed the Times Square Spectacolor Board to make a 45-second animated indictment. “America has a tickertape worm,” announced the first panel; the worm (Wall Street) gambles, gulps down a factory, and gradually swallows a flag-like continent, then runs away. The texts read: ” Wages Down, Malnutrition Up, Runaway Shops. Parasitic merger schemes cannibalize industrial America. Forcing towns to compete for fewer jobs and less work.” More complex than most of the boards (Which are sponsored by the Public Art Fund), Rupp’s was also more conscious of the need for directness and accessibility.

Rupp has always been a public artist in the best sense of the word. She informs, delights, works with and for an audience not limited to the art world, although her presence in galleries and art museums is also exemplary, providing other artists and viewers with innovative models for art that is actively involved with its site and society. The response to “Social Progress” was the stuff every public artist dreams of. Recently her proposal (a rare non-organic image of “clothing as construction,” cloth patterns coming together at the shoulder) has reached the short list for a monument to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in Union Square. She has received a New York City Percent for Art commission for a large piece in collaboration with the Coney Island Water Pollution Control Unit, a sewer works and water treatment plant, operated by the State Department of Environmental Protection. It is based on microscopic plants called tubeworms that thrive in sewage. They are hollow, and with their cilia, they take in toxins, digest them, and purify them. There are also horseshoe crabs, plentiful inhabitants of the site, whose forms may inspire lighting for the area. Rupp wants to glamorize and make more interesting and attractive the sewage creatures not considered “animate.”

Her most recently visible public piece was “The Insufficient Data Fish,” part of the “Noah’s Art” exhibition of animal sculptures in Central Park, fall 1989. Made entirely of masonite clipboards, the eleven-foot “Icthus Expertum” is a reminder that “swamps” are being replaced at the alarming rate of 500,000 acres per year by landfills and unbridled real estate speculation. Although wetlands are “Nature’s machinery of life,” they are more lucrative when transformed into dumps, condos, and expressway sites. All the un-used reports have engendered this “old monster, swimming around endlessly with no real purpose other than collecting information.” A dig at the liberal establishment, the fish is a well-meaning creature insatiably hungry for information; it never has enough, and never acts on what it has. (There is some relation here to another recent piece, “The Press Parrot,” complete with fedora, perched on a steel mock-up of a camera and tripod. The parrot is saying just what it has been taught to say, and nothing more, asking no hard questions of our so-called “Environmental President.”) Hovering above the reeds in the mini-wetlands around the pond near 59th Street, “The Insufficient Data Fish” was also a plea for bio-diversity, which Rupp linked to issues of cultural diversity raised by David Dinkins, New York’s first African American mayor.

The latest works, exhibited in March 1990 at PPOW, begin a new cycle for Rupp. Endowed with her usual humor and irony, they are formally cohesive as image and message at once. “Wave of the Future,” for example, is at first glance a beautiful object—a great metal snail-shell with translucent blue material, which turns out to be non-biodegradable plastic water bottles. Rupp collects them at the recycling center in the Bronx and has to scrub them ferociously to make them art-clean. Two other shells are “Synthetic Water” ( filled with green and white Perrier bottles, like an infected clam shell), and “Technobabble,” about scientific double-talk.

“99.4 Percent Forgotten” is elephant tusks made out of Ivory soap detergent bottles, a comment on elephants’ memory and their disappearance in a world unsympathetic to their environment. “Deep Sea Dinner” is a graceful dolphin filled with cat-food cans, and “Species Born—Agradable” is a frog bursting open to give violent birth to a garbage bag monster. (This is about the hype around so-called -biodegradable plastics which in fact need air to disintegrate, so they live forever in landfills—another successful attempt to baffle politicians and fool consumers by allaying their guilt.) “Life in a Landfill” is a handsome but ghostly tree trunk made of steel and stuffed with newspaper, compressed to look like bark and colored by rust. All this work reverses the industrial processes, returning the resources to their sources. It also suggests that things may look okay from the outside but the insides are increasingly rotten.

This is a conclusion any observant person must make when looking at the destruction wrought on the natural world, with no end in sight except The End. Yet Rupp rejects cynicism and chooses an activist option, Antoni Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” Her art gives pleasure even as it heralds the dire consequences of ignoring the pain we inflict on nature, which of course includes ourselves.

NB: All uncited quotations are from the artist in interviews with the author. January and March, 1990.

©christy rupp 1962–2025 | site by lisa goodlin design